Pain management for Patients & Clinicians

Overview

Trigeminal orofacial pain requires many management strategies as pain is so complex. Pain management will depend upon;

- It primarily involves sympathetic and compassionate consultation and specific skills in gaining the correct diagnosis

- Without a comprehensive history, examination, appropriate special tests and review; a correct diagnosis cannot be made

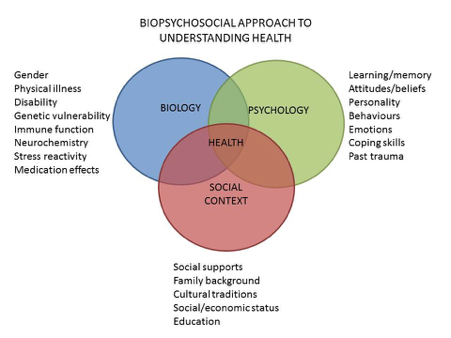

- management will depend upon the biological, psychological and environmental factors driving the pain suffering and behaviour

Many types of interventions will assist the patients in managing their pain.

- BJA management of orofacial pain

- Chronic Facial Pain

- OFP Current Persepective

- Pain Managment for Patients

Non-medical treatments including music, pet, acupuncture, meditation, hypnotism and other therapies can be effective and helpful depending upon the patient. Conventional treatments for orofacial pain include;

Consultation

- Being heard, reassurance, investigations, confirmation of diagnosis (if possible), understanding the expectations and time.

- education is a very important part of the consultation and in many studies has a significant pain relief effect

- ensure the patient has support and access to care

- getting the diagnosis right

- investigations may include

- radiology (Xrays plane films like a dental DPT or cone bean CT scan). MRI or medical CT

- bloods -haematology looking for systemic causes of your pain for example diabetes

Psychological (More here)

- CBT link to Pathway

- ACT link to virtual patient day

- Mindfulness (link to mindfulness doc)

Medical intervention (More here)

- Systemic medication

- Local medication

- Diagnostic blocks (More here)

- Therapeutic blocks

- Ona Botulinum Toxin

- Topical medication

- Capsaicin or lidocaine patches

Interventions

- Injections

- Greater occipital nerve blocks

- Diagnostic blocks

- Therapeutic blocks (More here)

- Botox for Ne pain and headaches

- Implanted pain control systems Implanted pain control systems involve inserting devices under your skin or elsewhere in your body. The devices use medicine, electric current, heat, or chemicals to numb or block pain.

- Intrathecal drug delivery sends medicine to the area of your pain.

- Electrical nerve stimulation uses electric current to interrupt pain signals.

- Neurostimulation

- Deep brain stimulation

- Nerve ablation destroys or removes the nerves that are sending pain signals.

- Chemical sympathectomy uses chemicals to destroy nerves. This treatment may be used for a type of chronic pain called complex regional pain syndrome, which affects the nervous system.

- Pulsed radiotherapy

- Gamma knife

- Decompression is a type of surgery used for nerve pain, such as from trigeminal neuralgia. The doctor cuts open your skin and then tries to move away blood vessels or other body structures that are pressing on nerves and causing pain.

- Microvascular decompression (only for Trigeminal neuralgia)

if you want more details go to Pain Management in the Education section and the following Links

- BJA management of orofacial pain

- Chronic Facial Pain

- OFP Current Persepective

- Pain Managment for Patients

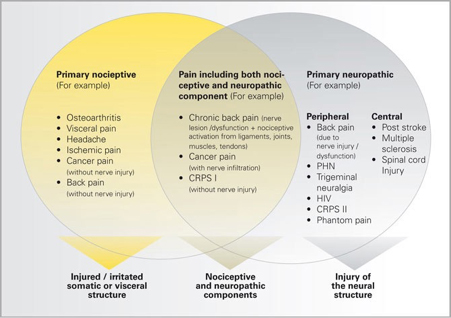

Pain management is complex to reflect the immense complexity of pain. Effective pain management will depend upon gaining the correct diagnosis. The type of pain must be recognised and investigated appropriately (see below).

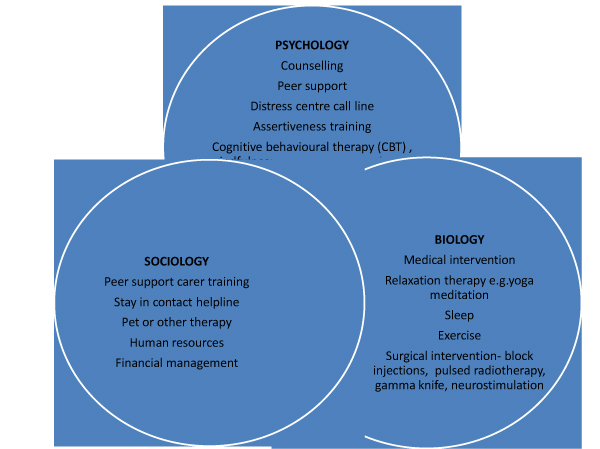

Pain management will also depend upon identifying the biological, psychological and environmental factors driving the pain suffering and behaviour:

Potential Management for various aspects of pain

Pain management can involve many aspects of care.

Overview management of chronic pain Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain

NICE guideline [NG193]Published: 07 April 2021 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG193 and https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193/documents/final-scope and https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign136.pdf

There are specific guidelines for the management of neuropathic pain Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings Clinical guideline [CG173]Published: 20 November 2013 Last updated: 22 September 2020 https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG173 and https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg173/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-4840898221

These guidelines are similar to those published elsewhere in the world (America, Canada, Australia and India)

Nociplastic pain requires separate considerations in diagnosis https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8347369/ and management https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00392-5/fulltext and https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29768305/

Temporomandibular Disorders

See the TMD Virtual Pain Day recordings (registration required)

- What to do about Jaw pain https://youtu.be/vxwbLsjU9us

- Self-management for TMD https://youtu.be/C8yBMXpFAAc

It’s important that people who have TMD play an active role in managing their symptoms. Self-management is key and there are both short and longer-term strategies that are recommended for managing the symptoms.

Short-term Short-term pain or flare-ups can be eased by:

- Over-the-counter painkillers (such as paracetamol or ibuprofen) taken on a regular basis for up to a week. If you have any other medical problems or are taking other medications and are unsure as to which painkillers you can take you can ask a pharmacist for advice.

- Applying heat and / or ice to the painful area to ease pain and reduce swelling.

- Gently massaging the muscles that move the jaw.

- Resting the jaw by temporarily switching to a ‘no-pain’ diet of soft food that doesn’t require chewing. After a maximum of 2 weeks normal foods should gradually be re-introduced.

Longer-term If symptoms persist after trying the short term advice you can try the following:

- Regular jaw exercises and relaxation can prevent the build-up of muscle tension and reduce or prevent pain from recurring.

- Building awareness and monitoring the early signs of stress and taking action to change the things that feed into it.

- Prioritising things that feel important and enjoyable which provides a ‘buffer’ against stress and protects against pain.

In addition to this, sometimes other treatments may also be helpful. It’s important to understand that these treatments will have the best chance of success when supported by a strong foundation of self-management as described above. Additional management options may include:

- An oral splint, you can see your dentist to have one of these made.

- Longer-term medications.

- sychological therapies including cognitive-behavioural therapy.

It is important to note that some treatments are not recommended. These include:

- Braces – TMD was once thought to be related to the position of the teeth but this view is not supported by the current evidence.

- Surgery – This is recommended in a very small number of cases which can easily be identified by a dental specialist. In most cases it is not indicated and likely to be harmful.

Primary Headaches. (More information here)

NICE recommendations here

Vitamin supplements (always seek advice from your family doctor or physician)

There is evidence that certain vitamins prevent migraines and may improve neuropathic pain in some patients. These are;

- Vitamin B2 Ribolflavin 400 Mgs daily or 100mgs twice daily

- Magnesium 400-500 mgs daily mst supplements are 200mg so take twice daily

- Vitamin D 000 international Units per week

- Co enzyme Q-10 100mg three times daily

- Melatonin may assist in enhancing sleep cycles and help reduce migraine frequency

Burning Mouth syndrome (More information here)

A Cochrane review on interventions for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome (Zakrzewska JM, Forssell H, Glenny A-M) states that there is insufficient evidence to show the effect of painkillers, hormones or antidepressants for ‘burning mouth syndrome’ but there is some evidence that learning to cope with the disorder, anticonvulsants and alpha-lipoic acid may help.

A burning sensation on the lips, tongue or within the mouth is called ‘burning mouth syndrome’ when the cause is unknown and it is not a symptom of another disease. Other symptoms include dryness and altered taste and it is common in people with anxiety, depression and personality disorders. Women after menopause are at highest risk of this syndrome. Painkillers, hormone therapies, antidepressants have all been tried as possible cures. This review did not find enough evidence to show their effects. Treatments designed to help people cope with the discomfort and the use of alpha-lipoic acid may be beneficial. More research is needed.

There is emerging evidence for topical clonazepam (Link to Clonazepm advice sheet)

Botoxin and CBD oil are being investigated (Link to CBD oil advice sheet)

Persistent idiopathic facial pain or PDAP (More information here)

The question is how do we treat a condition that we do not understand the basic causes? The lack of a clear pathophysiological basis precludes the establishment of a treatment protocol. The approach to the management of PIFP patients should consider patients’ beliefs on pain and the consequences of the pain disorder on their personal lives. Considering the psychiatric comorbidity, chronic course of disease in many patients, and the lack of drug treatment RCTs, a multidisciplinary approach encompassing the comorbidities is suggested, comparable to treatment concepts in other chronic headaches. Considering the chronicity and resulting distress, behavioral interventions are indicated. Accumulating evidence suggesting that PIFP may be a type of painful neuropathy underlies the preferential use of medications known to have an effect in painful neuropathies, i.e. antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs. Patient education is needed to clarify the diagnosis, and certainly the patient should be discouraged from any further invasive interventions aimed at pain relief in the absence of clear associated pathology.

Evidence basis for treatment of patients with PIFP is low level. Therapeutic trials of PIFP (and AFP) have been reported as efficient,

- using tricyclic antidepressants

- an open study on duloxetine

- a randomized controlled trial on venlafaxine

- open studies on anticonvulsants

- low level laser

There are no contraindications to non-interventional novel therapies (e.g. based on virtual reality or complementary and alternative medicine and these may be beneficial. Hypnosis might be a promising approach for therapy. However, the evidence for psychosocial interventions is limited, due to the lack of controlled studies. When all treatment fails, some have suggested pulsed radiofrequency treatment of the sphenopalatine ganglion, but this is based on an open trial in a small number of patients and there is no highlevel evidence for this or any other neurosurgical type of intervention. We do not recommend invasive procedures, as these always carry the risk for inducing a traumatic neuropathy and therefore may end up increasing pain.

Neuropathic Pain Management (More information here)

Trigeminal neuralgia (More information here)

International recommendations for patients with TN are aligned. Holistic management of the patient with reassurance, open contact for when regression periods end or when the condition is refractory. Addressing other health, sleep or psychological disorders is imperative.

- Classic TN with Neurovascular conflict

- Carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine ( if intolerance try gabapentin or lamotrigine)

- When medications either ineffective or side effects intolerance consider microvascular decompression

- Secondary TN

- Address cause for example MS or tumour

- Idiopathic TN

- Try medication decision tree for Classic TN

- If refractory may consider pain interventions for example Pulsed radiofrequency or ablative radiofrequency

Emerging strategies for TN include trigger zone anaesthesia and or Botox injections and Lidocaine patches can sometimes avail patients to undertake external activities that the otherwise might avoid.

Post herpetic neuralgia

A recent review (Hadley GR, Gayle JA, Ripoll J, Jones MR, Argoff CE, Kaye RJ, Kaye AD. Post-herpetic Neuralgia: a Review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016 Mar;20(3):17. doi: 10.1007/s11916-016-0548-x. Erratum in: Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016 Apr;20(4):28. PMID: 26879875.) Highlights the pharmacological treatment of PHN may include a variety of medications including alpha-2 delta ligands (gabapentin and pregabalin), other anticonvulsants (carbamazepine), tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline, doxepin), topical analgesics (5 % lidocaine patch, capsaicin) tramadol, or other opioids. The considerable side effect profiles of the commonly used oral medications often limit their practical use, and a combination of both topical and systemic agents may be required for optimal outcomes. Physicians and other treatment providers must tailor treatment based on the response of individual patients.

Post Traumatic neuropathic pain

Patients with PTNP often do not have knowledge about their treatment options, which can increase stress and anxiousness; therefore, communicating with patients and educating them on the diagnosis and treatment is an essential step in managing patients with PTNP (Kohli et al., 2020). The treatment of PTNP includes pharmacological, surgical, psychological therapies (Zuniga & Renton, 2016). (More information here)

Managing patients with PTNP is different to most other pain conditions, improvement of PTNP symptoms is difficult, and recurrence is frequent. Therefore, after a nerve injury happens, treatment options should be considered immediately as symptoms of PTNP may be recoverable in the first 3 to 6 months. After this, the symptoms can become permanent, at which point recovery is rare (De Poortere et al., 2021). Furthermore, Baad-Hansen and Benoliel (2017) stated that early treatment of PTNP can decrease the risk of permanent loss of sensation, further nerve damage, and pain. The treatment of PTNP patients should be based on the data collected during the assessment, pain, the level and effect of the nerve injury on patients’ quality of life. Therefore, the risk-benefit ratio of interventions must be considered before treatment (Renton & Van Der Cruyssen, 2019).

Psychological therapies – See link here

Management of patients with neuropathic pain requires a holistic approach. With a stratified approach one can identify factors contributing to reduced pain tolerance for example psychological disorders, sleep disorders, dietary factors etc. The mainstay of managing patients with refractory pain conditions id using psychological therapies (Link to Virtual patient pain day). Psychological therapies, such as CBT, adjunct to medical and surgical therapies are advantageous. CBT alone has shown to be successful in managing some PTNP patients as they could cope with the pain but not its impact on their life (Abrahamsen, Baad-Hansen, & Svensson, 2008; Renton & Yilmaz, 2012). Additionally, acupuncture, massage therapy and physical therapy can be used to manage post-traumatic neuropathic pain (Macone & Otis, 2018). Although the aim of available PTNP treatments is to reduce pain and psychological impacts in PTNP patients, the result of these treatments can be disappointing for patients and practitioners as permanent neuropathy has been reported in most affected patients (Renton & Yilmaz, 2012; Van der Cruyssen et al., 2020).

Psychological techniques – cognitive behavioural therapy has shown some benefit in the treatment of chronic pain. Studies of chronic pain management suggest that a combination of psychological, pharmacological and physical therapies, tailored to the needs of the individual patient, may be the best approach

Cognitive and behavioural therapies are both forms of psychotherapy (a psychological approach to treatment) and are based on scientific principles that help people change the way they think, feel and behave. They are problem-focused and practical. The term ‘cognitive behavioural therapy’ (CBT) has come to be used to refer to behavioural therapy, cognitive therapy and therapy that combines both of these approaches. The emphasis on the type of therapy used by a therapist can vary depending on the problem being treated. For example, behavioural therapy may be the main emphasis in phobia treatment or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) because avoidance behaviour or compulsive actions are the main problems. For depression the emphasis may be on cognitive therapy.

In 2005 the Government made a commitment to improve the availability of psychological therapies, the preferred method being cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for patients, especially in depressive and anxiety disorders. This led to the launch of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme in 2007, the benefits of which are beginning to come to fruition.

Behavioural therapy

This is a treatment approach based on clinically applying theories of behaviour that have been extensively researched over many years. It is thought that certain behaviours are a learned response to particular circumstances and these responses can be modified. Behavioural therapy aims to change harmful and unhelpful behaviours that an individual may have.

Cognitive therapy

This was developed later and focuses on clinically applying research into the role of cognitions in the development of emotional disorders. It looks at how people think about and create meaning about, situations, symptoms and events in their lives and develop beliefs about themselves, others and the world. These ways of thinking (harmful, unhelpful or ‘false’ ideas and thoughts) are seen as triggers for mental and physical health problems. By challenging ways of thinking, cognitive therapy can help to produce more helpful and realistic thought patterns.

Cognitive therapy was developed in the 1960s by Aaron Beck, an American psychiatrist. He felt that his patients were not improving enough through simple analysis and believed that it was their negative thoughts that were holding them back. At around the same time, another therapist, Albert Ellis, was also realising that people’s negative thoughts and irrational thinking could be underpinning mental health problems. He developed a form of cognitive therapy that has come to be known as rational emotive behavioural therapy (REBT).

Subtypes of cognitive therapy

- REBT: this is based on the belief that we all have sets of very rigid and perhaps illogical, beliefs that can make us mentally unhealthy. It teaches the patient to recognise and spot the beliefs that could be causing them harm and to replace them with more logical and flexible ones.

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT): this is another form of cognitive therapy that combines some of the ideas of cognitive therapy with the more analytical approach of psychodynamic psychotherapy. The client and the therapist work together to look at what has hindered changes in the past, in order to understand better how to move forward in the present. It was founded by Dr Anthony Ryle in the 1970s. The therapy sessions explore the patient’s past and childhood and determine why any problems have happened. They will then look at the effectiveness of any current coping mechanisms that the patient may have and will help the patient find ways to improve these. The work is very active. Diagrams and written outlines may be created to help recognise and challenge old patterns and coping mechanisms that do not work well, and provide revised mechanisms. There is a professional organisation known as the Association for Cognitive Analytic Therapy (ACAT) with a wealth of explanation about the therapy on the website (see link under ‘Further reading & references’, below).

- ACT Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)is a third wave behavioural therapy (along with Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy) that uses Mindfulness skills to develop psychological flexibility and help clarify and direct values-guided behaviour. ACT, does not attempt to directly change or stop unwanted thoughts or feelings, but aims to develop a new mindful relationship with those experiences to free a person up to be open to take action that is consistent with their chosen life values.

There is increasing evidence for ACT’s use with chronic pain in both a group and individual setting.

Vitamin supplements (always seek advice form your family doctor or physician)

There is evidence that certain vitamins prevent migraines and may improve neuropathic pain in some patients. These are;

- Vitamin B2 Ribolflavin 400 Mgs daily or 100mgs twice daily

- Magnesium 400-500 mgs daily mst supplements are 200mg so take twice daily

- Vitamin D 000 international Units per week

- Co enzyme Q-10 100mg three times daily

- Melatonin may assist in enhancing sleep cycles and help reduce migraine frequency

Medical management (Links to medication sheets here)

Chaparro, Wiffen, Moore, and Gilron (2012) stated that pharmacological treatments are important in the management of neuropathic pain. Additionally, researchers found and suggested that pharmacological treatment is useful in managing and reducing pain in PTNP patients after a nerve injury caused by dental implant placement (Park, Lee, & Kim, 2010). Opposingly, a study by Haviv, Zadik, Sharav, and Benoliel (2014) reported that only 10% of PTNP patients have shown pain reduction after pharmacological treatment. Chaparro et al. (2012) stated that combination therapy is recommended as it improves the effectiveness and reduces the risk of adverse effects. Furthermore, using topical medications can reduce the severity of post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathic pain and the risk of adverse effects (Heir et al., 2008). The adverse effects include weight gain, dizziness and dry mouth (Haviv et al., 2014).

Systemic medication

Damage to the somatosensory nervous system causes neuropathic pain in PTNP patients (Schlereth, 2020). There is an international consensus optimal medical interventions for patients with Neuropathic pain. Medical guidelines agree that first line medications should be Tricyclic antidepressants that were many decades ago, prescribed for depression in much higher doses, but due to their sdium channel blocking capacities work well for neuropathic pain in low doses, followed by pregabalin and gabapentin, both of which work on GABA receptors reducing pain transmission. Other medications including

- TCAs (i.e., amitriptyline) are suggested as the first-line therapy in patients with neuropathic pain (Finnerup et al., 2015; Szok, Tajti, Nyári, & Vécsei, 2019).

- Gabapentinoids (i.e., pregabalin and gabapentin)

- Serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (i.e., duloxetine and venlafaxine)

- Lamotrigine Kohli et al. (2020) stated that antidepressant and antiepileptic medications are the most commonly used medications to manage this condition.

- Weak opioids (e.g., tramadol and tapentadol) Local medication

All medication can cause side effects and man intolerant to patients Table 1 below.

Local medications

Botoxin: There is high level evidence for the therapeutic value of Botulinum Toxin Type A (BTX-A) as a peripheral prophylactic or symptomatic therapeutic nerve block for neuropathic pain (Attal N). There is level A evidence on the use of BTX-A in treating post-herpetic neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia and level B evidence in treating post-traumatic and painful diabetic neuropathic pain. In addition, BTX-A is relatively safe and effective with reversible effects is recommended for headache (NICE); migraines. Recent high level efficacy is also reported for and neuropathic orofacial pain conditions such as trigeminal neuralgia and post-herpetic neuralgia. Lower level evidence supports use of BtX-A for orofacial musculoskeletal disorders such as myofascial pain or hyperactivity, cervical dystonia and cervicalgia. When injected into the neuropathic painful location, the toxin can be taken up by peripheral terminals of nociceptive afferent nerve fibers, and this action suppresses peripheral and central release of algogenic neurotransmitters such as glutamate or substance P, thus promoting analgesia (Nathan Moreau, Wisam Dieb, Vianney Descroix, Peter Svensson, Malin Ernberg, Yves Boucher Topical Review: Potential Use of Botulinum Toxin in the Management of Painful Posttraumatic Trigeminal Neuropathy. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2017 Winter;31 (1):7-18.). However, here is extremely limited evidence available with regard treating trigeminal PTNP with Btx-A.

Topical medications

Topical capsaicin 8% has been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia, painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and HIV-neuropathy (Derry et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD007393, 2017). Topical lidocaine has been widely studied and found to reduce pain in patients with postherpetic neuralgia (Knezevic et al. Pain Manag 7:537-58, 2017). Although many other topical analgesics are available, there is limited data to support the efficacy of other agents. Topical analgesics are a relatively benign treatment for chronic pain conditions including neuropathic pain, musculoskeletal, and myofascial pain. There is evidence to support the use of topical NSAIDs, high concentration topical capsaicin, and topical lidocaine for various painful conditions (Jillian Maloney 1, Scott Pew 2, Christopher Wie 2, Ruchir Gupta 2, John Freeman 2, Natalie Strand 2 Comprehensive Review of Topical Analgesics for Chronic Pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep . 2021 Feb 3;25(2):7. doi: 10.1007/s11916-020-00923-2.).

- Capsaicin

- Lidocaine patches are second-line therapy in the treatment of this neuropathic pain (Szok et al., 2019).

- CPD oil (Advice sheet)

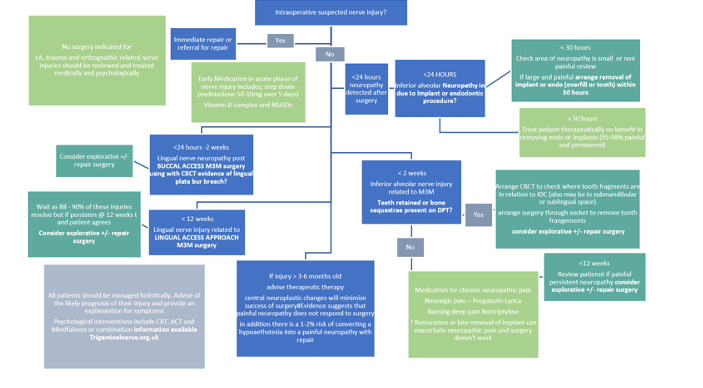

Surgery (see Figure 1)

Evidence remains poor for the efficacy of surgical intervention for trigeminal nerve injuries (Cochrane 2018). In general, it is accepted that neuropathic pain does not respond to surgery and this is often the main drive for the patient seeking care. As specific nerve injuries contradict surgical intervention (Local anaesthesia and chemical nerve injuries. Lingual nerve injury related t third molar surgery using lingual access approach has a high prevalence of temporary nerve injury and therefore the clinician should wait for the 88-90% of injuries to resolve. However, other nerve injuies related to Implant, Endodontics or third molar surgery should be managed swiftly in accordance with recommendations for spinal sensory nerve injuries.

Institution of early medical interventions, Prednisolone, Vitamin B complex and NSAIDS may minimise neural inflammation and prevent further neural damage (Trigeminalnerve.org.uk).

A study conducted by De Poortere et al. (2021) aimed to assess the benefits of surgical therapies in PTNP patients. The researchers observed an improvement in PTNP symptoms and reduction in the use of medication to manage PTNP following surgical therapies. A systematic review conducted by Kushnerev and Yates (2015) reported that surgical therapies should be considered if no improvement has been achieved after the first 3 months following the nerve damage, however, surgery could be delayed up to 6 months if ongoing improvement has been observed. Immediate surgery is sometimes required to resolve nerve injuries. For instance, if the nerve injury is caused by the placement of a dental implant or a root canal treatment, removal of the placed implant or root canal treated tooth should be considered within 30 hours to manage the nerve injury (Renton & Yilmaz, 2012).

Timing of surgical intervention

Immediate within 30 hour removal of Implant or endo is recommended

For third molar related nerve injuries Overall, the evidence is poor and ideally all pts should have immediate repair latest few days with CBCT scanning you can detect breech of the lingual plate and Frederic and I have been involved in developing MR neurrography which may also play a role in early detection ID nerve injuries…. both allowing for earlier intervention. we recommend immediate referral for LNIs and IANS. LNI we do a CBCT to look for lingual plate damage and for IANs we look for any teeth fragments or obvious canal damage and access through the fresh socket within 2 weeks maximum. Bagheri et al of 222 cases suggest 9 months max (Bagheri SC, Meyer RA, Khan HA, Kuhmichel A, Steed MB. Retrospective review of microsurgical repair of 222 lingual nerve injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010 Apr;68(4):715-23. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.111. Epub 2009 Dec 29. PMID: 20036042.)

Effectivity of nerve repair depends upon many factors primarily the site of damage (if the cell body is damaged there is no likelihood of recovery), duration of injury, cause of nerve injury, which nerve and patient factors (LINK 10)

- age of patient Younger better FSF recovery [Fagin AP, Susarla SM, Donoff RB, Kaban LB, Dodson TB. What factors are associated with functional sensory recovery following lingual nerve repair? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Dec;70(12):2907-15. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.03.019. Epub 2012 Jun 12. PMID: 22695009.]

- The younger age of patient and technique (Kang SK, Almansoori AA, Chae YS, Kim B, Kim SM, Lee JH. Factors Affecting Functional Sensory Recovery After Inferior Alveolar Nerve Repair Using the Nerve Sliding Technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Aug;79(8):1794-1800. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2021.02.036. Epub 2021 Mar 1. PMID: 33781730.)

- presence of neuropathic pain

It is well accepted that neuropathic pain does not respond to surgery in general and more specifically trigeminal nerve injuries (zuniga & Renton LINK 18)

- Zuniga JR, Yates DM. Factors Determining Outcome After Trigeminal Nerve Surgery for Neuropathic Pain. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Jul;74(7):1323-9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.02.005. Epub 2016 Feb 18. PMID: 26970144.

- Zuniga JR, Yates DM, Phillips CL. The presence of neuropathic pain predicts postoperative neuropathic pain following trigeminal nerve repair. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014 Dec;72(12):2422-7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.08.003. Epub 2014 Aug 11. PMID: 25308410.

- Bagheri SC, Meyer RA, Cho SH, Thoppay J, Khan HA, Steed MB. Microsurgical repair of the inferior alveolar nerve: success rate and factors that adversely affect outcome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Aug;70(8):1978-90. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.08.030. Epub 2011 Dec 16. PMID: 22177818.

Renton Egbuniwe Nerves and Nerve Injuries Vol 2: Pain, Treatment, Injury, Disease and Future Directions 2015, Pages 469-491

- Renton T Van der Cruyssen F Diagnosis, pathophysiology, management and future issues of trigeminal surgical nerve injuries November 2019 Oral Surgery 13(4)

- Which nerve responds best? Simon Aitkins recently published a series of LNI patients from Sheffield showing positive results ( not explicitly pain relief) in patients undergoing LN repair (Atkins S, Kyriakidou E. Clinical outcomes of lingual nerve repair. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Jan;59(1):39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.07.005. Epub 2020 Aug 13. PMID: 32800402.) Similar to two other studies on lingual nerve (Leung YY, Cheung LK. Longitudinal Treatment Outcomes of Microsurgical Treatment of Neurosensory Deficit after Lower Third Molar Surgery: A Prospective Case Series. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 4;11(3):e0150149. LINK 19 :29 cases presented by my PhD Student Frederic in Leuven (LINK20)

Management of nerve injuries is summarised in Figure 1

Side effects of drugs commonly used for NePain control

| Drug | Contraindications | Main Side effects |

| Tricyclic AntidepressantsAmitriptylineNortriptyline10mg nocte raising 10 mg per week up to 40mg nocte-maintenance dose | Cardiac conduction abnormalities, recent cardiac events, narrow-angle glaucoma, elderly patients, epilepsy, bipolar disorder. TCAs may enhance the response to alcohol and the effects of barbiturates and other CNS depressants | dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, sedation, weight gain |

| SRNIsDuloxetineVenlafaxine | pregnancy | nausea, dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, insomniaheadache, nausea, sweating, sedation, hypertension, seizures |

| SSRIs Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorsFluoxetine | pregnancy | Side effects: nausea, sedation, decreased libido, sexual dysfunction, headache, weight gain |

| Anti epileptics | ||

| TegretolCarbamazepine | liver disease, acute intermittent porphyria, hyponatremia, a serious blood disorder, marrow depression, taken an MAO inhibitor within the past 14 days8% rashes that may be very serious are more likely to occur in persons with a particular gene called “HLA-B*1502”. This gene occurs almost exclusively in patients with ancestry across broad areas of Asia, including South Asian Indians. Patients with ancestry from these areas should have a blood test by their physician to see if they have the “HLA-B*1502” gene before starting treatment | dizziness, diplopia, nauseaTreatment can result in aplastic anaemia. |

| Pregabalin | renal impairment, diabetes, Congestive heart failure, suicide ideation | drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, sedation, weight gain |

| Gabapentin | renal impairment, elderly, suicide ideation | drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, sedation, weight gain |

| Lamotrigine | avoid abrupt withdrawal, renal impairment, hepatic impairment, suicide risk, pregnancy 1st trimester | dizziness, constipation, nausea; rarely, life-threatening rashes |

TCA= tricyclic antidepressants, GP = Gabapentin, PGB Pregabalin Dulox= Duloxetine

Suggested Mechanisms of Action for Antidepressants and Antiepileptic Drugs Used to Treat Chronic Pain

| Mechanism of action | Drugs |

| Inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake | Tricyclic antidepressants (secondary amines): desipramine (Norpramin), nortriptyline (Pamelor) |

| Inhibition of norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake | Tricyclic antidepressants (tertiary amines): amitriptyline (Elavil), imipramine (Tofranil) |

| Novel antidepressants: venlafaxine (Effexor), duloxetine (Cymbalta) | |

| Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) | |

| Blockade of sodium channel | Antiepileptic drugs: carbamazepine (Tegretol), gabapentin (Neurontin), lamotrigine (Lamictal) |

| Blockade of calcium channel | Antiepileptic drugs: gabapentin, pregabalin (Lyrica)* |

| Enhancement of γ-aminobutyric acid | Antiepileptic drug: carbamazepine |

| Spasmolytic drug: baclofen (Lioresal) |

*—Investigational drug (approval pending from U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Surgical interventions for pain (Link 10 and 11 refractory pain)

Trigeminal neuralgia is the singular chronic Orofacial pain condition where surgery is indicated when medical management is ineffective. Nd there are indications for early surgical repair in some PTNP patiens.

- Microvascular decompression for refractory TN patients

- Radiofrequency ablation

- Stereotactic radiosurgery

- Gamma knife may be indicated If there is medical contraindications to MVD

Microvascular Decompression

If you suffer from the severe pain of trigeminal neuralgia, you probably have tried a number of medications and therapies to find relief. If other treatments have failed and you are considering surgery, microvascular decompression may help you. This surgery technique has been performed for decades. Today, our team at the UCLA Neuromodulation for Movement Disorders and Pain Program is the best choice for expert surgical care in Los Angeles.

What is microvascular decompression?

Microvascular decompression is a minimally invasive procedure that involves removing or relocating any blood vessels putting pressure on the trigeminal nerve.

Am I a candidate for microvascular decompression at UCLA?

At the UCLA Neuromodulation for Movement Disorders and Pain Program, we perform microvascular decompression to treat chronic pain caused by trigeminal neuralgia. This pain condition has several possible causes. We only perform microvascular decompression when the pain involves pressure on the trigeminal nerve.

The procedure is best for patients 65 and younger who have no significant medical or surgical risk factors.

What happens during microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia?

Trigeminal neuralgia is often caused by pressure on the trigeminal nerve from a blood vessel, usually the superior cerebellar artery. During this minimally invasive procedure, your neurosurgeon makes an incision behind your ear to reach the trigeminal nerve. Working with tiny instruments through this hole, your surgeon carefully moves any arteries touching the nerve and removes any veins pushing against it. Your surgeon will place a pad between the vessel and nerve to prevent them from touching again.

What to expect after microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia

The incidence of facial numbness after microvascular decompression is much less than with radiofrequency ablation. Pain relief can be long-lived and effective:

- Up to 90 percent of patients experience complete relief

- Pain recurs in 5 to 17 percent

All surgeries have risks. Possible complications after microvascular decompression include:

- Aseptic meningitis, with head and neck stiffness

- Major neurological problems, including deafness and facial nerve dysfunction

- Mild sensory loss

- Cranial nerve palsy, causing double vision, facial weakness, hearing loss

- On very rare occasions, postoperative bleeding and death

Radiofrequency Ablation

from http://neurosurgery.ucla.edu/site.cfm?id=1354

At the UCLA Neuromodulation for Movement Disorders and Pain Program, our team performs radiofrequency ablation to treat chronic pain conditions, such as trigeminal neuralgia. While this surgery can’t cure your condition, it can ease your pain and make life more enjoyable.

What is radiofrequency ablation for trigeminal neuralgia?

Ablation is a medical term that refers to the removal of tissue. Radiofrequency ablation, or RFA, is a surgical technique that directs high-frequency heat onto targeted areas of the body, such as tissues, tumors and – in the case of chronic pain – nerves.

If you suffer from trigeminal neuralgia, your neurosurgeon uses radiofrequency ablation to target the trigeminal nerve, destroying its ability to transmit pain signals to your brain.

Am I a candidate for radiofrequency ablation surgery at UCLA?

The first line of treatment for trigeminal neuralgia is medication. If you suffer from severe facial pain and do not respond well to medication, your doctor may recommend radiofrequency ablation surgery.

What happens during radiofrequency ablation for trigeminal neuralgia?

Patients are awake and asleep at different times during radiofrequency ablation for trigeminal neuralgia. Here’s what you should expect:

- While you are asleep under general anesthesia, your neurosurgeon will carefully place a needle through the corner of your mouth to reach the trigeminal nerve at the base of the skull.

- After X-rays confirm the needle is in place, your neurosurgeon will wake you up, stimulate the nerve and ask if you feel the stimulation in the same place where you experience pain. This step confirms that your doctor has targeted the right location.

- After you are put back to sleep, your neurosurgeon uses radiofrequency heat to slightly injure the nerve just enough that it causes some facial numbness and tingling and takes the pain away.

What to expect after radiofrequency ablation

- This procedure works in 70-80 percent of patients

- 50 percent of patients will experience recurrent pain in two years

The treatment can be repeated if pain recurs.

Stereotactic Radiosurgery

from http://neurosurgery.ucla.edu/site.cfm?id=1356

In the UCLA Neuromodulation for Movement Disorders and Pain Program, stereotactic radiosurgery is used as a treatment option for essential tremor and trigeminal neuralgia, a pain disorder. When you choose our program, your care is in the hands of the most expert team in Los Angeles. Our multidisciplinary approach brings together neurosurgeons, neurologists and radiation oncologists. Meet our team.

What is stereotactic radiosurgery?

Stereotactic radiosurgery is a noninvasive, outpatient operation that delivers high focal radiation on a target – such as lesions on the brain or the trigeminal nerve – without damaging the surrounding brain and spine.

Stereotactic radiosurgery is different from traditional radiotherapy because radiation is delivered in a very focused manner, sparing the rest of the brain from significant radiation exposure. Stereotactic radiosurgery delivers the radiation in one session. Unlike most techniques for stereotactic radiosurgery, at UCLA, we use an advanced image-guided frameless technique to deliver this precise radiation so that we don’t have to fix a frame to your head.

Stereotactic radiosurgery for essential tremor

Thalamotomy by stereotactic radiosurgery is an effective treatment option for involuntary movements associated with essential tremor. Using this procedure, a very high dose of focused energy is delivered to a precise part of the thalamus, an area of the brain that regulates movement. This is the same part of the brain that is targeted with deep brain stimulation.

Stereotactic radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia

Stereotactic radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia focuses radiation on the trigeminal nerve, damaging it enough to block pain signals to the brain. This procedure has a success rate of greater than 70 percent and has few side effects. Pain may return in up to 50 percent of patients, who can be treated again.

What happens during stereotactic radiosurgery?

No incisions are necessary with stereotactic radiosurgery. You can expect:

- A very detailed and precise MRI of your brain that your doctor will use to plan precisely where to deliver the radiation

- A special CT scan of your head with a mask helps your doctor keep track of your head during treatment and precisely deliver radiation to the right spot

- UCLA’s Novalis Shaped Beam Surgery system, considered the Gold Standard for shaped-beam radiosurgery, will focus high doses of radiation on the target site

What to expect after stereotactic radiosurgery

After this non-invasive treatment, patients are able to walk out of the clinic and carry on with their lives right away. Because it is non-invasive, it can take between 2 days and 6 weeks before you may see any benefits. Most patients who respond to therapy have long-term improvement. In some cases, symptoms can return and the treatment may need to be repeated.

Gamma Knife Trigeminal Neuralgia Treatment

from http://www.neurosurgery.pitt.edu/centers-excellence/image-guide-neurosurgery/trigeminal-neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN), also known as tic douloureux, is a pain syndrome recognizable by patient history alone. The condition is characterized by intermittent one-sided facial pain. The pain of trigeminal neuralgia typically involves one side (>95%) of face (sensory distribution of trigeminal nerve (V), typically radiating to the maxillary (V2) or mandibular (V3) area). Physical examination findings are typically normal; although mild light touch or pin perception loss has been described in central area of the face. Significant sensory loss suggests that the pain syndrome is secondary to another process, and requires high-resolution neuroimaging to exclude other causes of facial pain.

The mechanism of pain production remains controversial. One theory suggests that peripheral injury or disease of the trigeminal nerve increases afferent firing in the nerve perhaps by ephaptic transmission between afferent unmyelinated axons and partially damaged myelinated axons; failure of central inhibitory mechanisms may also be involved. Blood vessel-nerve cross compression, aneurysms, chronic meningeal inflammation, tumors, or other lesions may irritate trigeminal nerve roots along the pons. Uncommonly, an area of demyelination, such as may occur with multiple sclerosis, may be the precipitant. In some cases, no vascular or other lesion is identified rendering the etiology unknown. Development of trigeminal neuralgia in a young person (<45 years) raises possibility of multiple sclerosis, which should be investigated. Thus, although trigeminal neuralgia typically is caused by a dysfunction in the peripheral nervous system (the roots or trigeminal nerve itself), a lesion within the central nervous system may rarely cause similar problems.

Medical Management

The goal of pharmacologic therapy is to reduce pain. Carbamazepine (Tegretol) is regarded as the most effective medical treatment. Additional agents that may benefit selected patients include phenytoin (Dilantin), baclofen, gabapentin (Neurontin), Trileptol and Klonazepin.

Surgical Management

Prior to considering surgery, all trigeminal neuralgia patients should have a MRI, with close attention being paid to the posterior fossa. Imaging is performed to rule out other causes of compression of the trigeminal nerve such as mass lesions, large ectatic vessels, or other vascular malformations.

The surgical options for trigeminal neuralgia include peripheral nerve blocks or ablation, gasserian ganglion and retrogasserian ablative (needle) procedures, craniotomy followed by microvascular decompression (MVD), and stereotactic radiosurgery (Gamma Knife®).

Percutaneous transovale needle techniques include radiofrequency trigeminal electrocoagulation, glycerol rhizotomy, and balloon microcompression. Microvascular decompression (MVD) is often preferred for younger patients with typical trigeminal neuralgia. High initial success rates (>90%) have led to the widespread use of this procedure. This procedure provides treatment of the cause of trigeminal neuralgia in many patients. Percutaneous techniques are advocated for elderly patients, patients with multiple sclerosis, patients with recurrent pain after MVD, and patients with impaired hearing on the other side, however some authors recommend needle techniques as first surgical treatment for many patients. It is generally agreed that MVD provides the longest duration of pain relief while preserving facial sensation. In experienced hands, MVD can be performed with low morbidity and mortality. Most authors offer MVD to young patients with trigeminal neuralgia.

Trigeminal Neuralgia Radiosurgery

Radiosurgery is performed by delivering a high dose of ionizing radiation in a single treatment session using multiple beams precisely focused at the target inside the brain. Several reports have documented the efficacy of Gamma Knife®‚ stereotactic radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia . Because radiosurgery is the least invasive procedure for trigeminal neuralgia, it is a good treatment option for patients with co-morbidities, high-risk medical illness, or pain refractory to prior surgical procedures.

Between 1992 and 2007, a more than 750 radiosurgical procedures for TN were performed at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Our report summarizes the long-term outcome in 220 patients who had undergone Gamma Knife® radiosurgery for idiopathic, longstanding pain refractory to medical therapy. One hundred and thirty-five patients (61.4%) had prior surgeries including microvascular decompression, glycerol rhizotomy, radiofrequency rhizotomy, balloon compression, peripheral neurectomy, or ethanol injections. Eighty-six patients (39.1%) had one, 39 (17.7%) had two, and ten (4.5%) had three or more prior operations. For the other 85 patients, radiosurgery was the first surgical procedure. A maximum dose of 70 to 80 Gy was used.

The outcome of pain relief was categorized into four results (excellent, good, fair, and poor). Complete pain relief without the use of any analgesic medication was defined as an excellent outcome. Complete pain relief with still requiring some medication was defined as a good outcome. Partial pain relief (>50% relief) was defined as a fair outcome. No or less than 50% pain relief was defined as a poor outcome. Most patients responded to radiosurgery within six months (median, two months). At the initial follow-up within six months after radiosurgery, complete pain relief without medication (excellent) was obtained in 105 patients (47.7), and excellent and good outcomes were obtained in 139 patients (63.2%). Greater than 50% pain relief (excellent, good, and fair) was obtained in 181 patients (82.3%).

Complications after Radiosurgery

The main complication after radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia was new facial sensory symptoms caused by partial trigeminal nerve injury. Seventeen patients (7.7%) in our series developed increased facial paresthesia and/or facial numbness that lasted longer than 6 months.

Repeat Radiosurgery

Trigeminal neuralgia patients who experience recurrent pain during the long-term follow-up despite initial pain relief after radiosurgery can be treated with second radiosurgery procedure. The target is placed anterior to the first target so that the radiosurgical volumes at second procedure overlaps with the first one by 50%. We advocate less radiation dose (50 to 60 Gy) for second procedure, because we believe that a higher combined dose would lead to a higher risk of new facial sensory symptoms.

Indications for Radiosurgery

The lack of mortality and the low risk of facial sensory disturbance, even after a repeat procedure, argue for the use of primary or secondary radiosurgery in this setting. Repeat radiosurgery remains an acceptable treatment option for trigeminal neuralgia patients who have failed other therapeutic alternatives.