Chronic Pain

Summary

- Diagnosis of orofacial pain can be complex.

- Some tips are provided for differentiating neuropathic from inflammatory pain.

- Principles of management of orofacial pain are outlined.

- Simple strategies are highlighted that will assist the clinician in managing these often-complex cases.

Introduction

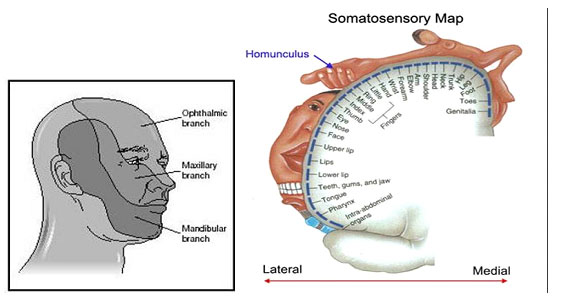

Orofacial pain is pain within the trigeminal system. The trigeminal nerve supplies general sensory innervation to face, scalp, and mouth. A vast proportion (over 40%) of the sensory cortex represents the trigeminal input (Fig. 1). Thus persistent pain in the orofacial region has significant impact on the sufferer resulting in both functional and psychological consequences (see more).

Figure 1 Left illustrates domains where each of the trigeminal nerve branches supply the face with sensation (we call them dermatomes) The figure on the right shows how much of the brain sensory cortex is dedicated to feeling sensory feedback from the face head and mouth

The trigeminal sensory region is very complex, incorporating the cranium, ears, eyes, sinuses, nose, pharynx, infratemporal fossa, jaw joint, teeth, jaws, salivary glands, oral mucosa, and skin. As many medical students are rarely exposed to ear, nose and throat (ENT), otolaryngology, and dentistry, this region remains an enigma to most, with their singular experience of trigeminal pain being based on trigeminal neuralgia in relation to neurosurgical procedures.

Chronic pain is defined as pain that persists after inflammatory response to the acute causes of pain has ceased. Increasingly Chronic pain is perceived as a disease entity in itself with evidence of structural (gray matter loss), neurophysiological and genetic changes within the neuromatrix. The chronic pain encompasses two broad categories; nerve derived ‘neuropathic’ pain (e.g. headaches and neuralgias) and refractory persistent inflammatory pain (e.g. Arthritis) (WOOLF Lancet 99 and WOOLF 2010).

Chronic pain is common affecting 30% of the adult population (100 million in IS alone) and impacting both the individual and society with estimated costs of $635 billion each year in medical treatment and lost productivity.1

Chronic Trigeminal Pain

Chronic orofacial pain syndromes represent a diagnostic challenge for any practitioner. Patients are frequently misdiagnosed or attribute their pain to a prior event such as a dental procedure, ENT problem or facial trauma. Psychiatric symptoms of depression and anxiety are prevalent in this population and compound the diagnostic conundrum. Treatment is less effective than in other pain syndromes, thus often requires a multidisciplinary approach to address the many facets of this pain syndrome.2

Aetiology of orofacial pain

Facial pain can be associated with pathological conditions or disorders related to somatic and neurological structures. There are a wide range of causes of chronic orofacial pain and these have been divided into three broad categories by Hapak et al 19942 and Woda et al 2005:3

- Neurovascular

- Neurological (see more)

- Idiopathic

(with Arthromyalgic pain conditions non clustering) 3

The commonest cause of chronic orofacial pain is temporomandibular disorders, principally myofascial in nature.

As mechanisms underlying these pains begin to be identified, more accurate mechanism-based classifications may come to be used. A major change in mechanism has been that burning mouth syndrome probably has a neuropathic cause using the newly defined definitions, rather than being a pain owing to psychological causes.

Incidence

Chronic orofacial pain is comparable with other pain conditions in the body, and accounts for 20-25% of chronic pain conditions.1,4,5 A six-month prevalence of facial pain has been reported by between 1%4 and 3%4 of the population. In the study by Locker and Grushka,5 some pain or discomfort in the jaws, oral mucosa, or face had been experienced by less than 10% in the past four weeks.

A recent report estimated that 20% of American adults (42 million people) report that pain or physical discomfort disrupts their sleep a few nights a week or more.6 When asked about four common types of pain, respondents of a National Institute of Health Statistics survey indicated that low back pain was the most common (27%), followed by severe headache or migraine pain (15%), neck pain (15%) and facial ache or pain (4%).6 Most population-based studies have shown that women report more facial pain than men1,4,5 with rates approximately twice as high among women compared to men. In clinical populations the rates for women are even higher.2 On the other hand, other studies have found no sex difference in the prevalence of orofacial pain. Several studies have also shown variability in the prevalence across age groups. The age distribution of the facial pain population differs from that of the most usual pain conditions. In contrast to chest and back pain, for example, facial pain has been suggested to be less prevalent in older age.4

Diagnosis

The International Headache Society (IHS) has published diagnostic criteria for primary and secondary headaches as well as facial pain.7 Criteria have also been published by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).8 The impact of trigeminal pain must not be underestimated. Consequences include interruption with daily social function such as eating, drinking, speaking, kissing, applying makeup, shaving, and sleeping.9 Burning mouth syndrome has been reported to cause significant psychological impact in 70% of patients5 and 29% of patients experiencing temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain report high disability resulting in unemployment.4

Systemic disorders that may contribute or cause chronic orofacail pain must be excluded (Table 2). In addition signs of sinister (neoplastic diseasemust be recognised and urgently referred as appropriate (Table 3).

Many orofacial pain conditions may mimic toothache (Table 4) and the GDP must always consider neuropathic pain as a possible cause of ‘refractory toothache’ so that irreversible and damaging treatment, done with the best intention, is avoided.

Necessary investigations include haematological (Table 5) and radiographic examinations. Routine panorals are the first view of choice o exclude local disease. Often if the patient presents with neuropathy, neuralgia type symptoms MRI may be required to exlucde space occupying lesions, demyelinations (Multiple sclerosis) and vascular compromise (for TN Patients) see Figure 2 a-c.

A table is provided to summarise the differential diagnosis for chronic trigeminal pain (Table 6).

Classification of Orofacial Pain

See more information here and here.

The aim of this section is to outline the causes of chronic orofacial pain (lasting >3 months). However, the most common causes of acute dental pain are trauma or infection of the dental pulp which contains the nerves and vessels supplying the tooth.

See table illustrating a suggested classification for chronic orofacial pain.

Chronic orofacial pain

Several classifications of chronic orofacial pain have been presented and they do conflict with each other. The author will use the mechanistic based classification by Woda et al3 for this chapter as it presents a pragmatic and clinically useful tool.

Group 1: Neurovascular (predominantly ophthalmic division [V1] pain)

Headaches comprise most of this group of conditions. A recent NICE guidance and pathways.10

Migraine

Migraines are perhaps the most studied of the headache syndromes. This is due in part to the high incidence and significant loss of productivity and limitation on quality of life suffered by those with the syndrome.9 It is estimated that 17% of women and 6% of men have migraine headaches. Onset is usually in the second or third decade.9

Characteristics of migraine include:10

- Five or more lifetime headache attacks lasting 4–72 hours each and symptom-free between attacks, moderate to severe pain, unilateral with or without aura visual signs.

- The female-to-male ratio is 3:1.

- It is unilateral but can be bilateral.

- The pain has a throbbing quality and feels as if it is associated with a pulse.

- Photophobia, phonophobia, and osmophobia are features of migraine, as is nausea.

- The pain worsens with exertion and improves with sleep.

- The patient may or may not experience aura.

Pharmacological therapy includes abortive and preventative medications, depending on the frequency and severity of the headaches. Abortive agents include serotonin agonists, ergotamine, isometheptene, and anti-inflammatories. Preventative agents

include antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and angiotensin receptor blocking agents.

Tension-type headaches

Tension-type headache (TTH) is the most common type of headache.10 It occurs in 69% of men and 88% of women over a lifetime, and the annual prevalence is 63% in men and 88% in women. TTH can be further be distinguished as ‘episodic’ TTH (ETTH) or ‘chronic’ TTH (CTTH). The distinction is made largely on frequency of occurrence (<15 days a month for Migraine and > 15 days a month for TTH).

Characteristics of tension-type headache include:

- Highest socioeconomic impact, affecting 30–78% of the population.

- At least 10 episodes, occurring less than one day a month on average.

- Infrequent episodes lasting from 30 minutes to seven days.

- Typically bilateral.

Medication overuse headaches

This is a newly-recognised phenomenon that may characterise the majority of headache patients in the West (30–78%).8 It is recognised that long term ingestion of over-the-counter analgesics can result in a compromised pain resistance.

Chronic daily headache

Chronic daily headache (CDH) is described as headache occurring at least six days a week for a period of at least 6 months.10 The pain is usually present throughout the day with little time spent pain-free. The head pain is typically bilateral, frontal or occipital, non-throbbing and moderately severe. The syndrome is associated with the overuse and abuse of many common over-the counter pain medications (aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, etc.), barbiturates, and opioid analgesics. A careful history will reveal an increasing need for medications and the emergence of a chronic headache that is qualitatively distinct from the headache for which it was originally taken. This led to the idea of CDH being a ‘transformed migraine’.

Trigeminal autonomic cephalgias

(including Cluster headache and short lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT))

Cluster headache (CH) is characterised by intensely severe pain (sometimes termed suicide headache) with boring or burning qualities located unilaterally in the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal area.10,11

Characteristics of cluster headaches include;

- The male:female ratio is 6:1.

- The onset of pain is sudden.

- Unilateral orbital, supraorbital or temporal.

- Severe episodic pain lasting 15-180 minutes.

- Up to eight times a day to every other day for a period of 2-12 weeks.

- The pain is characterized as severe, boring, and burning.

- It awakens the patient from sleep and does not improve with rest. Many individuals pace and may injure themselves because of the severity of the pain.

- Associated symptoms include ipsilateral conjunctival injection, tearing, and nasal congestion.

Abortive treatment includes oxygen, sumatriptan injections, and/or dihydroergotamine. Preventative treatment includes verapamil, lithium, divalproex sodium, and topiramate.

Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiaform conjunctival irritation and tearing (SUNCT) is possibly a variation of the cluster tic syndrome. It is characterized by brief (15–120 seconds) bursts of pain in the eyes, temple, or face. The pain is usually unilateral and is described as burning, stabbing, or electric. It occurs frequently in a 24-hour period (>100 episodes). Neck movements can trigger the pain. SUNCT syndrome is refractory to medical therapy but there is increasing evidence for treatment with lamotrigine.11

Temporal arteritis

Temporal arteritis is characterised by daily headaches of moderate to severe intensity, scalp sensitivity, fatigue,and various non-specific complaints with a general sense of illness. Ninety-five per cent of patients are over 60 years old.12 The pain is usually unilateral, although some cases of bilateral or occipital pain do occur. Pain may also be felt in the tongue and is a continuous ache with superimposed sharp, shooting head pains. The pain is similar to and may be confused with that of CH, but CH tends to occur in younger patients. The two may also be distinguished on physical exam, when dilated and tortuous scalp arteries are noted. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is markedly elevated in temporal arteritis. Definitive diagnosis is made by artery biopsy from the region of the pain, although negative biopsy may be caused by the spotty nature of the disease and does rule out the diagnosis. High dose steroid therapy usually precipitates a dramatic decrease in head pain. Failure to respond to steroid therapy with a negative biopsy should call the diagnosis into question. If the diagnosis seems likely based on history and physical examination, steroids should be started immediately to avoid vision loss, the most common complication of the disorder, occurring in 30% of untreated cases. The biopsy remains positive for 7–10 days from starting steroid therapy. Steroids may be tapered to an every other day maintenance schedule when the pain resolves and ESR normalizes. The disease is usually active for 1–2 years, during which time steroids should be continued to prevent vision loss.11

Group 2a: Neuralgia (primary and secondary neuropathies)

Group 2 includes primary neuropathies (trigeminal neuralgia (typical or atypical), glossopharyngeal neuralgia) and secondary neuropathies (including postherpetic neuralgia and post-traumatic V neuralgia). Other peripheralneuropathies affecting the trigeminal system (nutritional neuropathy, diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), chemotherapy, and multiple sclerosis (MS) are not covered in this review but can present as orofacial pain.

Trigeminal neuralgia (typical or atypical)

Typical trigeminal neuralgia is characterised by severe bursts of lancinating pain in one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve. Bursts are quick, repetitive, electric shock-like sensations with paroxysmal pain attacks lasting from a few seconds to less than two minutes. The pain is severe and distributed along one or more of the branches of the trigeminal nerve with a sudden, sharp, intense stabbing or burning quality. Between attacks the patient is completely asymptomatic without gross neurological defects. The pain may be precipitated from trigger areas or with certain daily activities such as eating, talking, washing the face or brushing the teeth. Attacks are the same in an individual patient. If there is no specific trigger zone or the pain lasts longer than seconds, then atypical trigeminal neuralgia may be diagnosed. Structural causes of facial pain should be excluded. The syndrome is most common in patients over 50 years. The course may fluctuate over many years, and remissions of months or years are not uncommon.

Aetiology

The cause in 60–88% of cases is vascular compression of the trigeminal ganglion leading to demyelination and hence ‘short-circuiting’ of A-b fibres with A-d and C-fibres. In a smaller group of patients, trigeminal neuralgia is symptomatic due to tumours, arteriovenous malformations (A-V) and MS. International guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia have recently been published.13

Features

The presence of trigeminal sensory deficits, bilateral involvement, and abnormal trigeminal reflexes may indicate the presence of symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia due to tumours, A-V malformations and multiple sclerosis. Younger age of onset, involvement of the first division, and unresponsiveness to treatment do not correlate consistently with symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia. Abnormal trigeminal reflexes are associated with an increased risk of symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia and should be considered useful in distinguishing symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia from classic trigeminal neuralgia. Routine head imaging identifies structural causes in up to 15% of patients.13

Treatment

The first-line treatments of choice are anticonvulsant medication. Carbamazepine remains the gold standard drug but there is now evidence that oxcarbazepine is equally effective and has improved tolerability, although full randomised controlled trials (RCT) have not been published. Baclofen and lamotrigine may be considered useful.12 More recently, a RCT using Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines reported that gabapentin, together with weekly injections of ropivacain into the trigger area number, yielded a number needed to treat of 2.4 (50% reduction of pain) at 4 weeks.12 There is only limited data to help patients decide when to have surgery but often the factors used are refractoriness to medical therapy and loss of tolerability. Surgery such as microvascular decompression or radiofrequency gangliolysis offers good results although there is associated long-term morbidity of facial paraesthesia that can be a major complaint among patients. A wide variety of surgical techniques are available. Gasserian ganglion percutaneous techniques, gamma knife, and microvascular decompression are all options. Microvascular decompression may be considered over other surgical techniques to provide the longest duration of pain freedom, but it is the most invasive procedure. Results from gamma knife therapy, although non-invasive, show nerve damage, and sensory loss can sometimes develop six months after the procedure has been performed. It can be disturbing in 5% of patients and there are patients who have developed anaesthesia dolorosa.

The role of surgery versus pharmacotherapy in the management of trigeminal neuralgia in patients with MS remains uncertain. A decision analysis study done with 156 patients with trigeminal neuralgia showed that surgical techniques narrowly offer the highest chance of maximising patient quality of life. However, surgery is not right for everyone, and patients should be informed about their full range of choices. Patients are keen to remain informed about trigeminal neuralgia as shown by their attendance at conferences and the demand for specific printed patient-orientated information.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is characterized by pain attacks similar to those in trigeminal neuralgia, but islocated unilaterally in the distribution of the glossopharyngeal nerve. Pain is most common in the posteriorpharynx, soft palate, base of tongue, ear, mastoid or side of the head. Swallowing, yawning, coughing orphonation may trigger the pain. Management is similar to that for trigeminal neuralgia.134

Group 2b: Secondary neuropathies

Many conditions can cause peripheral sensory neuropathies that may present with pain,14 these include:

- Diabetes

- Post herpetic neuralgia

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- Chemotherapy

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Post-surgical traumatic neuropathy

- Parkinson’s

- Malignancy

- Drugs – Growth hormone injections

- Nutritional neuropathy

The most common causes of trigeminal neuropathy would include post-traumatic neuropathy, post herpetic neuralgia (PHN) and idiopathic persistent post-surgical pain.

Postherpetic neuralgia

In patients over 50 years of age there is a 60% incidence of developing postherpetic pain.16 Herpetic skineruption is caused by the reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus from the sensory nerve ganglia. The reactivated virus is carried via the axons distally to the skin where it produces a painful rash with crusting vesicles in a dermatomal distribution. The trigeminal nerve is the second most commonly affected after nerves in the thoracic region. Ramsay Hunt syndrome occurs when herpes zoster infection of the geniculate ganglion causes earache and facial palsy.

Pain that persists two or more months after the acute eruption is known as post herpetic neuralgia. The pain is neuropathic in nature, severe, and it is associated with allodynia and hyperalgesia, most commonly affecting the VI distribution of the trigeminal nerve. High doses of antivirals, steroids, and amitriptyline are often used for the acute eruption in otherwise healthy individuals. Antivirals, NSAIDs, and opiates are often used in immunocompromised patients. More recently, there is evidence that topical 5% lignocaine patches (Versatis) worn alternatively every 12 hours are very effective.17

Post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy

The most problematic outcome of dental surgical procedures, with major medico-legal implications, is injury to the trigeminal nerve.18 The prevalence of temporarily impaired lingual and inferior alveolar nerve function is thought to range between 0.15–0.54% whereas permanent injury caused by injection of local analgesics is much less frequent at 0.0001–0.01%.18 Traumatic injuries to the lingual and inferior alveolar nerves may induce a pain syndrome owing to the development of a neuroma. The most commonly injured trigeminal nerve branches, the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves are different entities, whereby the lingual nerve sits loosely in soft tissue compared with the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN), which resides in a bony canal. Injury to the third division of the trigeminal may occur due to a variety of different treatment modalities, such as major maxillofacial and minor oral surgery.18 Peripheral sensory nerve injuries are more likely to be persistent when the injury is severe, if the patient is older, if the time elapsed between the cause of the injury and the review of the patient is of longer duration, and when the injury is more proximal to the cell body.

Subsequent to iatrogenic trigeminal nerve injury, the patient often complains about a reduced quality of life, psychological discomfort, social disabilities and handicap.19 Patients often find it hard to cope with such negative outcomes of dental surgery since the patient usually expects significant improvements not only regarding jaw function, but also in relation to dental, facial, and even overall body image after oral rehabilitation. Altered sensation and pain in the orofacial region may interfere with speaking, eating, kissing, shaving, applying makeup, tooth brushing and drinking; in fact just about every social interaction we take for granted as discussed. In a recent prospective assessment of 252 patients with iatrogenic trigeminal nerve injuries19 most were caused by third molar surgery but implants and local anaesthesia were significant contributors.

The diagnosis of posttraumatic neuralgia/neuropathy is based upon a history of surgery or trauma temporally correlated with the development of the characteristic neuropathic pain. Age, poor wound closure, infections, foreign material in the wound, haematoma, skull fracture, diabetes mellitus or peripheral neuropathy elsewhere in the body predispose to neuroma development. The pains commonly persist for months after the injury and can be permanent. Medical therapy is similar to that used in neuropathic pain conditions depending on the patients’ symptoms. 70% of patients presented with pain.19 This highlights the problems related to postsurgical neuropathy aggravated by the fact that many patients may not have been warned at all about nerve injury or told that they would risk numbness.

Traumatic injuries to peripheral nerves pose complex challenges and treatment of nerve injuries must consider all aspects of the inherent disability. Pain control is of paramount importance and rehabilitation needs to be instituted as first-line treatment. Early intervention is important for optimal physiologic and functional recovery.19Reparative surgery may be indicated when the patient complains of persistent problems related to the nerve injury, however there remains a significant deficiency in evidence base to support this practice. The patients’ presenting complaints may include functional problems due to the reduced sensation, intolerable changed sensation or pain, the latter being predominantly intransigent to surgery.19 Less often highlighted is the psychological problems relating the iatrogenesis of the injury and chronic pain. Generally for lesions of the peripheral sensory nerves in man the ‘gold standard’ is to repair the nerve as soon as possible after injury. However, the relatively few series of trigeminal nerve repair on human subjects relate mainly to repairs undertaken at more than six months after injury.19

It is evident from the literature review that there needs to be a cultural change in the choice of intervention, timing and outcome criteria that should be evaluated for interventions for trigeminal nerve injuries. To date, there have been a very limited number of prospective randomised studies to evaluate the effect of treatment delay, the surgical, medical or counselling outcomes for trigeminal nerve injuries in humans.

Persistent post-surgical pain without demonstrable neuropathy

This is defined as present at one year post-op or longer, unexplained by local factors and best described as neuropathic in nature.

Nonodontogenic dentolalveolar pain is often difficult to diagnose because it is poorly understood.20 Even defining and categorising such persistent pain is challenging. Nonodontogenic pain is not an uncommon outcome after root canal therapy and may represent half of all cases of persistent tooth pain. A recent systematic review of prospective studies reported that reported the frequency of nonodontogenic pain in patients who had undergone endodontic procedures.20 Nonodontogenic pain was defined as dentoalveolar pain present for six months or more after endodontic treatment without evidence of dental pathology. The endodontic procedures reviewed were nonsurgical root canal treatment, retreatment, and surgical root canal treatment. 770 articles retrieved and reviewed, 10 met inclusion criteria with a total of 3,343 teeth were enrolled within the included studies and 1,125 had follow-up information regarding pain status. We identified nonodontogenic pain in 3.4% (95% confidence interval, 1.4%-5.5%) frequency of occurrence.20

The prevalence of persistent pain post-surgically in the trigeminal system may be low compared with other surgical sites. However when one considers the significant frequency of dental surgical procedure undertaken then significant numbers of individuals may be affected by both post-traumatic neuropathy and persistent post-surgical pain.

Risk factors for developing persistent post surgical-pain include;

- Genetics (catecholamine-O-methyltransferase)

- Preceding pain (intensity and chronicity)

- Psychosocial factors (ie. fear, memories, work, SES, physical levels of activity, somatization)

- Age (older = ↑ risk)

- Gender (female = ↑ risk)

- Surgical procedure and technique (tension due to retraction).19

All these persistent post-surgical pain conditions may be attributable to post-traumatic neuropathy but it is difficult to be conclusive without a demonstrable neuropathic area in relation to the previous surgery. The significant decreased incidence in this condition in the trigeminal region may reflect the lack of central sensitisation due to most procedures being undertaken under local anaesthetic.

Group 3: Idiopathic chronic orofacial pain

This group includes preauricular pain related to the Temporomandibular joint disorders, burning mouth syndrome (BMS), and persistent idiopathic facial pain.

Temporomandibular joint pain

See separate section.

Burning mouth syndrome

Burning mouth syndrome is defined as an intraoral burning sensation or other dysaesthesia for which no medical or dental causes can be found and in which the oral mucosa is of grossly normal appearance.20 Many patients will also have subjective dryness, parasthesia and altered taste which initiates spontaneously not related to any intervention. The psychological morbidity is high and the patients often display high HADS (Hospital Anxiety and depression scale) scores.5 This is understandable when considering that these patients experience high levels of constant pain of unknown aetiology, severely affecting their quality of life.21

The aetiology of BMS remains controversial suggested causes include; sychogenic factors, hormone disorders, neuropathic alterations, oral phantom pain, neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation). However there is increasing evidence to show that BMS is primarily a neuropathic pain with secondary psychological features.

Diagnosis of BMS is by exclusion21 and suggested screening includes saliva tests, psychometrics, histological, candidal counts and, most importantly, blood tests. These may be used to establish the possible causes of systemic and local causes for the patient’s symptoms. Routine blood tests may include;

- Nutritional neuropathy: deficiencies may occur due to dietary deficiency, malabsorption, and or haemorrhage. Possible factors include; Fe, Ferritin, B1, B2, B3, B6, Folate, B12, Zinc, Ca [calcium], Phosphates and vitamin E.

- Blood dyscrasias (WBC, RBC, Ht, MCV, ESR)

- Chronic liver disease/Alcoholic liver disease (LFTs -Tot protein, albumin, bilirubin, Alk phos,AST,ALT, cholesterol)

- Kidney disease (KFTs – Urea, creatinine)

- Endocrine disease (Diabetes (RBG), Cortisol, Oestrogen, Thyroid function)

- Connective tissue disease (ANA, ENA)

- Gastro intestinal disease, Gastric reflux (helicobacter)

- Other: Inflammatory factors (IL6, IL2, Sub P. NKA,CGRP), Allergy IgE, Parkinson’s disease and gluten-sensitivity neuropathy (coeliac disease).

Management remains difficult due to the lack of understanding about the basic underlying biological mechanisms, as well as high quality randomised control trials. To date the only evidence-based intervention is cognitive behavioural therapy but commonly topical clonazepam, tricyclic antidepressants, pregabalin or gabapentin may be moderately effective for these patients.21

Persistent idiopathic facial pain

The term atypical facial pain was first introduced in 1924. It has since been renamed persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP).22 PIFP refers to pain along the territory of the trigeminal nerve that does not fit the classic presentation of other cranial neuralgias.8 The duration of pain is usually long, lasting most of the day (if not continuous). Pain is unilateral and without autonomic signs or symptoms. It is described as a severe ache, crushing or burning sensation. Upon examination and workup no abnormality is noted.

Definition

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP),8 chronic facial pain refers to symptoms which have been present for at least six months. ‘Atypical’ pain is a diagnosis of exclusion after other conditions have been considered and eliminated (ie it is idiopathic), and is characterised by chronic, constant pain in the absence of any apparent cause in the face or brain. Many information sources suggest that all ‘unexplained’ facial pains are termed atypical facial pain but this is not the case. Categories of idiopathic facial pain conditions include neuropathic pain due to sensory nerve damage, chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS) from sympathetic nerve damage and atypical facial pain.

Epidemiology

Atypical facial pain is more common in women than in men; most patients attending a facial pain clinic arewomen aged between 30 and 50 years. Although any area of the face can be involved, the most commonlyaffected area is the maxillary region. In the majority of patients there is no disease or other cause found. In a few patients the symptoms represent serious disease. In a small number of patients the pain may be oneconsequence of significant psychological or psychiatric disease.

Clinical presentation

Atypical facial pain has a very variable presentation. Often it is characterised by continuous, daily pain of variable intensity. Typically, the pain is deep and poorly localised, is described as dull and aching, and does not awaken the patient from sleep. At onset the pain may be confined to a limited area on one side of the face, while later it may spread to involve a larger area. The pain is not triggered and is not electrical in quality. Intensity fluctuates but the patient is rarely pain-free. Pain is typically located in the face and seldom spreads to the cranium in contradistinction to tension headache. It is more common in women aged 30–50 years old. Between 60 and 70% of these patients have significant psychiatric findings, usually depression, somatisation or adjustment disorders, therefore psychiatric evaluation is indicated.

Treatment usually involves antidepressants, beginning with low dose amitriptyline (or Nortriptyline) at bedtime and increasing the dose until pain and sleep are improved. Accurate figures are difficult to obtain because of the lack of agreement on classification criteria. Estimated incidence is 1 case per 100 000 population, although this number may be underestimated. PIFP affects both sexes approximately equally, but more women than men seek medical care. The disorder mainly affects adults and is rare in children. PIFP is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion. Daily or near-daily headaches are a widespread problem in clinical practice. According to population-based data from the United States, Europe, and Asia, chronic daily headache affects a large number (approximately 4–5% of the population) of patients. Importantly, PIFP must be distinguished from various other chronic daily headache and orofacial pain syndromes.

A careful history and physical examination, including a dental consultation, laboratory studies, and imaging studies, may be necessary to rule out occult pathology. Underlying pathology such as malignancy, vasculitis, infection, and central or peripheral demyelination may manifest early as neuralgia, and, not until focal neurological deficits, imaging abnormalities, or laboratory abnormalities are discovered, does the diagnosis become evident. Rarely cases of referred pain must also be considered.

Medical care

Medical treatment of PIFP is usually less satisfactory than medical treatment for other facial pain syndromes. Medications used to treat PIFP include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, substance P depletion agents, topical anaesthetics, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists, and opiate medications. Of these classes of medications, anticonvulsants and antidepressants appear to be the most effective. The neuropathic component of pain responds well to anticonvulsants and antidepressants. Pharmacotherapeutic knowledge is paramount in the treatment of this refractory pain syndrome. A multimechanistic approach, using modulation of both ascending and descending pain pathways, is frequently necessary. The goal of therapy is to manage the pain effectively with the fewest adverse medication effects. Alternative therapies such as acupuncture and neuromuscular re-education have been tried and should be considered as part of a comprehensive treatment plan. Psychiatric treatment is important in the overall management of a patient with chronic pain. Available data on alternative treatments are limited.

Surgical care

Details of neurosurgical interventions are beyond the scope of this book. Analgesic surgery should be consideredat a centre well versed in these procedures.

Consultations

Psychometric testing may be of benefit in the evaluation and treatment of patients with headache and facial pain. Many tests have been applied, but probably the most widely used is the Minnesota multiple personality inventory (MMPI). While especially useful in the evaluation of chronic headache and facial pain patients, a thorough discussion of psychometric testing is beyond the scope of this book and is mentioned here only for completeness. Consultation with a dentist may be of benefit. All treatments should be provided in co-operation with the patient’s primary care physician.

Atypical odontalgia (AO)

AO is characterised by continuous, dull, aching, or burning pain of moderate intensity in apparently normal teeth, or endodontically treated teeth, and occasionally in extraction sites. AO is not usually affected by testing the tooth and surrounding tissues with cold, heat or electrical stimuli. The pain remains constant despite repeated dental treatment, even extractions in the region, often rendering patients with persistent pain but whole quadrants stripped of dentition. Moreover, the toothache characteristics frequently remain unchanged for months or years, contributing to the differentiation of AO from pulpal dental pain. Occasionally, the pain may spread to adjacent teeth, especially after extraction of the painful tooth.

These patients are defined as having pain in a tooth or tooth region in which no clinical or radiological findings can be detected. Several studies have been conducted to define this group more clearly. AO patients have more comorbid pain conditions, higher scores for depression and somatisation, significant limitation in jaw function, and lower scores on quality of life measures when compared with controls. When compared to patients with TMD, AO patients were more likely to describe their pain as aching, find rest relieving but cold and heat aggravating. Over 80% relate the onset of their pain to dental treatment The author believes that the relationship with previous surgical intervention implies that this condition may, in some cases, be partial postsurgical neuropathy as described in the previous group.

The lack of RCTs makes evidenced-based care in AO difficult. One of the major problems with this condition is convincing the patient, and informing their dentist, that there are no dental causes for their pain, so avoiding unnecessary irreversible invasive dental treatment. AO patients are often diagnosed late and therefore need a multidisciplinary approach. In her recent review,23 Baad-Hansen presents a sensible progressive approach to managing AO, beginning with topical lignocaine or capscasian, then TCAs (Trcyclic antidepressants). Ultimately, the drugs used in neuropathic pain are often gabapaentin and pregablin, and finally tramadol or oxycodone.

Conclusion

Chronic orofacial pain continues to present a diagnostic challenge for many practitioners. Patients are frequently misdiagnosed and they suffer from psychiatric symptoms of depression and anxiety. Treatment is less effective than in other pain syndromes and a multidisciplinary approach treatment is desirable.

References

- Institute of medicine USA 2011 report on pain Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint – Institute of Medicine

- Hapak L, Gordon A, Locker D, Shandling M, Mock D, Tenenbaum H C. Differentiation between musculoligamentous, dentoalveolar and neurologically based craniofacial pain with a diagnostic questionnaire Journal of Orofacial Pain 1994; 8: 357–68.

- Woda A, Tubert-Jeannin S, Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fleiter B, Goulet JP, Gremeau-Richard C, Navez ML, Picard P, Pionchon P, Albuisson E. Towards a new taxonomy of idiopathic orofacial pain. Pain 2005; 116:396–406.

- Lipton J A, Ship J A, Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Ass 1993; 124: 115-21.

- Locker D, Grushka M. The impact of dental and facial pain. J Dental Research 1987; 66: 1414-7.

- National Centers for Health Statistics, Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans 2006, Special Feature: Pain.

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus06.pdf. - Benoliel R, Birman N, Eliav E, Sharav Y. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: accurate diagnosis of orofacial pain? Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 752-62.

- Türp J C, Hugger A, Nilges P, Hugger S, Siegert J, Busche E, Effenberger S, Schindler H J on behalf of the German Chapter of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Recommendations for the standardized evaluation and classification of painful temporomandibular disorders: an update. Schmerz 2006; 20: 481-9.

- Mathew P G, Garza I. Headache. Semin Neurol 2011; 31: 5-17. Epub 2011.

- NICE Guidance and pathways http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/headaches#path=view%3A/pathways/headaches/diagnosis-of-headaches.xml&content=close

- Cittadini E, Matharu M S. Symptomatic trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Neurologist 2009;15: 305-12.

- Affolter B, Thalhammer C, Aschwanden M, Glatz K, Tyndall A, Daikeler T. Difficult diagnosis and assessment of disease activity in giant cell arteritis: a report on two patients. Scand J Rheumatol 2009; 38:1-2.

- Zakrzewska J M. Medical management of trigeminal neuropathic pains. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010;11: 1239-54.

- Teixeira M J, de Siqueira S R, Bor-Seng-Shu E. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia: neurosurgical treatment and differential diagnosis. Acta Neurochir 2008; 150: 471–5.

- Benoliel R, Eliav E. Neuropathic orofacial pain. Oral Maxillofacial Surgical Clinics of North America 2008; 20: 237–254, vii.

- Baron R, Binder A, Wasner G. Neuropathic pain: diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment.Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 807-19.

- Baron R, Mayoral V, Leijon G, Binder A, Steigerwald I, Serpell M. Efficacy and safety of 5% lidocaine (lignocaine) medicated plaster in comparison with pregabalin in patients with postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic polyneuropathy: interim analysis from an open-label, two-stage adaptive, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Drug Invest 2009; 29: 231-41.

- Hillerup S. Iatrogenic injury to the inferior alveolar nerve: etiology, signs and symptoms, and observations on recovery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008; 37: 704–9.

- Renton T, Yilmaz Z. Managing iatrogenic trigeminal nerve injury; A case series and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011 in press.

- Nixdorf N, Moana-Filho E J, Law A S, McGuire L A, Hodges J S, John M T. Frequency of Nonodontogenic Pain after Endodontic Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Endod 2010; 36: 1494-8.

- Klasser G D, Fischer D J, Epstein J B. Burning mouth syndrome: recognition, understanding, and management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2008; 20: 255-71, vii.

- Evans R W, Agostoni E. Persistent idiopathic facial pain. Headache 2006; 46: 1298–1300.

- Baad-Hansen L, Pigg M, Ivanovic SE, Faris H, List T, Drangsholt M, Svensson P. Intraoral somatosensory abnormalities in patients with atypical odontalgia-a controlled multicenter quantitative sensory testing study.Pain. 2013 Apr 6. doi:pii: S0304-3959(13)00160-7. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.04.005. [Epub ahead of print]