Orofacial pain resembling primary headaches

An Update on Headaches for the Dental Team

P Chana, T Renton

Pain is often the reason many patients seek help from the dental team. Although dental pain is likely to be the most common cause, chronic pain conditions such as headaches may also show similar symptoms to toothache resulting in mis management and delayed diagnosis. A high number of patients experience headaches and they are often debilitating to patients. Despite this, dentists have a lack of knowledge about headaches or neurovascular pain. The dental team should be able to identify when the pain is likely to be of neurovascular origin rather than persistent intermittent toothache, and the team could provide advice and an appropriate referral if necessary. This should help reduce unnecessary dental treatment and improve the pain relief to these long-suffering patients.

Headaches can present like a toothache or sinusitis causing ain in the midface and these conditions are recognised in the new international classification of orofacial pain.

Midfacial pain is a particular presentation where bye primary headache disorders for example, Migraine or Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias – otherwise known as Cluster headache conditions, must be excluded.

More information in links below:

Many clinicians would diagnose midfacial pain as Rhinosinusitis however sinusitis is rarely painful and more likely to be migraine (more information here).

A systematic approach to differential diagnostics is presented here.

CPD/ Clinical relevance

We aim to improve the knowledge of the dental team, especially general dental practitioners, in relation to primary headaches such that neurovascular pain can be differentiated from odontogenic causes of pain. We also aim to provide general dental practitioners with the knowledge of how to initially manage the pain if it is neurovascular in origin in primary care.

Objectives

The dental team should be able to identify when the pain is likely to be of neurovascular origin rather than odontogenic pain. The dental team should also be able to initially manage the pain if neurovascular in origin.

Introduction

Pain in the head and neck region is often the driving factor for patients to seek care from the dental team. It is not rare for chronic orofacial pain conditions to manifest with similar symptoms to dental pain. This can often lead to a misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment resulting in complications for both the clinician and the patient(1). Diagnosis and management of these patients can be particularly challenging; however, a correct diagnosis is mandatory to ensure patient safety and care.

Headaches are predicted to affect up to 46% of the worldwide population and they have been ranked as being one of the top 10 most disabling disorders(2). Therefore, the implications to health care and the patients should not be underestimated. The International Headache Society updated their classification in 2018(3). It is those that fall into the group of ‘primary headaches’ which are most relevant and may be encountered by the dental team, however an awareness of the other types may also be beneficial. A general overview of the classification is shown in Table 1 at the end of the page.

Due to the high number of patients who experience headaches and that the pain experienced may mimic dental pain it is important that dental teams are able to correctly identify these disorders as they will be nonresponsive to routine care and if appropriate, may need referral on for urgent care. In general, dentists have a poor knowledge of headaches and often struggle with this. In this paper we aim to improve the knowledge of the dental team, especially general dental practitioners, in relation to primary headaches and discuss how they can be differentiated from odontogenic causes of pain. This should help reduce misdiagnosis, and the number of irreversible procedures being carried out which are routinely used to treat odontogenic pain. We also aim to provide general dental practitioners with the knowledge on how to initially manage neurovascular pain in primary care.

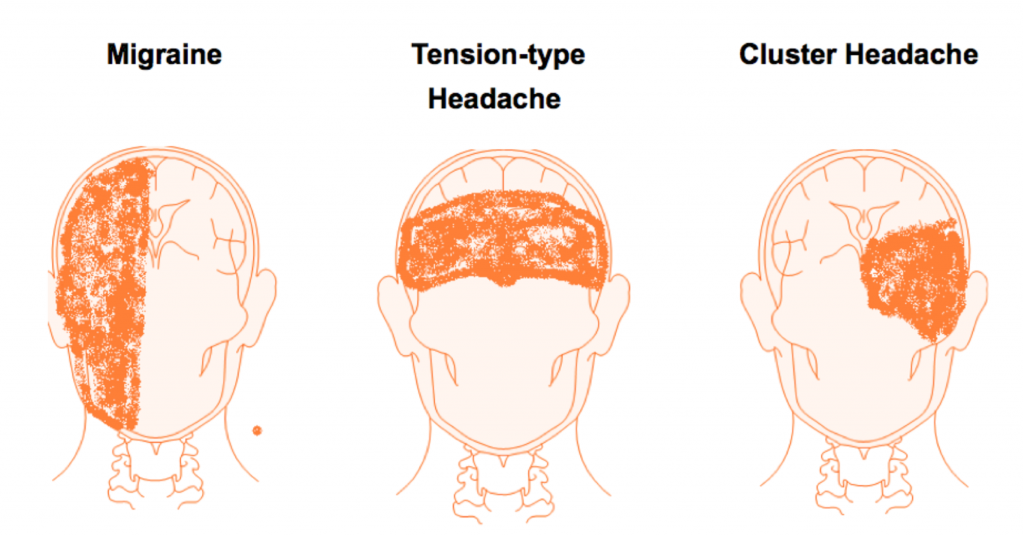

Migraines

Migraines have been ranked as the third most prevalent disease in the world, so it is likely that dentists will encounter these patients (3). Two main types exist, those with an aura and those without. Other types of migraines have been discussed in a previous paper suitable for dentists2. The diagnostic criteria for migraines has been defined by the International Headache Classification (Table 2 at the end of the page). Migraines are more common in females, occur in all ages from childhood and have a unilateral distribution of pain (Figure 1 at the end of the page). They can last up to days and may be triggered by certain foods, alcohol, stress, the contraceptive pill or hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle (4). Approximately, 20% of patients will experience an aura prior to the headache. Auras may be visual and examples include zig zag patterns, flashes of light or loss of vision. They may also be sensory such as tingling or numbness which can spread over the face, lips and tongue (5).

It is also of note to the reader that migraines may cause an increased risk of cardiovascular events, most commonly stroke, especially in women who smoke and take oestrogen supplements. They have also been linked to cerebrovascular disorders such as seizures. All of which should also be taken into account when managing these patients (6).

The patient should also be questioned sensitively about depression and anxiety; both of these have been linked to migraines likely due to the common pain receptors involved in both. A presence of these disorders has been shown to reduce compliance with prescribed medications and advice on management (6).

Common Differential Diagnoses:

- Odontogenic Pain

- Sinus Pain

- Temporomandibular joint disorder

Migraines most commonly cause pain in the V1 distribution, but they may also cause pain in the V2 and V3 distribution, occasionally independent of pain in V11 (7). Due to the distribution of pain presenting in the V2 and V3 region, dentists may be confused and misdiagnose the pain has having a dental or sinus origin.

There is also a well-established link between temporomandibular joint disorders and migraines due to the similar neurophysiological processes involved in both conditions (8). Although this may complicate the diagnosis of the patients’ pain, if this is found to be the case it is suggested that they should be managed using a simultaneous approach to both conditions, rather than managing each OFP condition separately (9).

Reference documents

- Autonomic signs migraine overlap

- Headache – 2013 – May – Diagnosis and Clinical Features of Trigemino‐Autonomic Headaches

- Migraine 10 steps

- Migraine OFP

- Migraine

- Sleep and migraine

Treatment:

General Dental Practitioners:

General dental practitioners may give patients advice on acute treatment which aims to offer patients a reduction in the pain and other symptoms experienced with a treatment goal of reducing the disability associated with migraines. The evidence favours NSAIDS (aspirin, diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen), triptans, ergotamine derivatives and opioids such as butorphanol. A combination of medications is also well supported in the literature with a triptan and NSADS being more effective than pairing a triptan with paracetamol (10). Despite the evidence supporting the benefits of using opiods in migraines, NICE doesn’t recommend that they should be prescribed to patients due to side effects and risk of dependence (10). Of note, NSAIDs can result in gastrointestinal and cardiovascular adverse effects so they should be used with caution. In addition, triptans should be avoided in patients with coronary artery disease, poorly controlled hypertension and other peripheral vascular diseases. Newer medications are being developed to overcome the vascular contraindications of triptans.

Specialist referral treatment:

Treatment to prevent migraines, normally provided by a specialist in the field, is considered based on the frequency of migraines experienced and the level of disability. The following medications have an established evidence base for their efficacy in preventing migraines: antiepileptic drugs, triptans and hypotensives including; beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol). In comparison antidepressants and other beta-blockers such as atenolol may also be considered but there is less evidence to support the use of these drugs (11). Although gabapentin may have been previously recommended, guidelines updated in 2019 by NICE have advised that it should not be offered to patients (1,10).

Emerging treatments for the prevention of migraines include injectable therapies which can be administered both subcutaneously and intravenously such as botulinumtoxinA and monoclonal antibodies but there are still questions over their long-term safety (11). Neuromodulation is also an emerging active treatment for migraines which may be suitable for patients who are not responding to drug therapy or have contraindications (11,12).

Biobehavioural therapy such as cognitive behaviour therapy should also not be ignored. In more recent years there is a growing body of evidence to support their use in chronic pain as well as migraines (11). Further evidence has shown that using these techniques alongside drug therapy has been shown to be more effective than using drugs alone (13).

Tension-type headaches

Tension-type headaches (TTH) are the most common type of headache experienced by patients and thought to affect up to 78% of the population (2,3). Their diagnostic criteria can also be seen in Table 2. The mild to moderate pain tends to be bilateral and a pressing or tightening pain (Figure 1). This is a non-pulsating pain, in comparison to a migraine which often has a pulsating type pain (2). TTH can be further classified into episodic and chronic which has been elaborated on in Table 2. In very rare cases, a tension headache can show similar symptoms to concerning conditions such as a subarachnoid haemorrhage, TIA or stroke.

Common Differential diagnoses

- Temporomandibular joint disorders including headache attributed to TMD

The pain experienced during a tension type headache may be confused with temporomandibular joint disorder pain caused by bruxism, especially as the temporalis may be tender to palpate, and sinus disease (14).

The relationship between bruxism and TTH should be acknowledged by the dental team and recent evidence supports an association between the two (15). A proposed modern theory is that TTH may result from referred pain from trigger points in head and shoulder muscles. Bruxism may be a factor in the development of trigger points in the head and neck region. It is these trigger points are responsible for central sensitisation which has noted to be present in TTH 15. Further to this, patients who suffer from TTH also report heavier tooth contact, muscle tension, stress, and more pain in their head region (16).

Treatment

General Dental Practitioners:

The mild to moderate pain experienced by patients can be managed with analgesics which may be prescribed by their general dental practitioner if deemed suitable. The effectiveness of analgesics is reduced if the patient frequently experiences TTH. As a first line treatment, acetaminophen (paracetamol) may be prescribed which is favourable due to the reduced gastric side effects and as a second line ibuprofen can be prescribed.

Specialist referral treatment:

For patients suffering from chronic TTH, drug therapy can be used to reduce the frequency and severity of headaches. Tricyclic antidepressants are most widely used, with amitriptyline found to be the most effective (17,18). Mirtazapine may also be used. Other types of antidepressants such as SSRI and tetracyclic are not indicated in these patients. Botulinum toxin A has also been licensed for use however there is a lot of conflicting evidence supporting this as a treatment modality and further research is needed to be undertaken in this area (18).

As with migraines, a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments (physical and/or pscyhologic therapy such as CBT) has been shown to be more effective than using one treatment alone (17, 18). Although the links to bruxism have been discussed, dentists should not routinely use an occlusal splint to treat TTH due to the lack of supporting evidence as a treatment modality (17, 19).

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

The trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are composed of a group of short lasting and unilateral headaches that also present with cranial autonomic features which are lateralised and ipsilateral to the headache (20). These include cluster headaches, paroxysmal hermicrania, short-lasting unilateral neuralgia headache attacks and hemicrania continua (3). Despite these headaches being rare, these patients may present in a dental setting and due to the extremely debilitating nature of these headaches it is important they can be appropriately managed.

The presenting pain is an intense unilateral pain with neuralgic multiple stabbing events which lasts several hours and spontaneously regresses leaving the patient with pain free interludes. The pain episodes often occur several times a day at the same times usually early mornings and clusters of pain most commonly occurring in spring and autumn (1). There are associated autonomic signs which include: drooping of the eyelid (ptosis), redness of the cheek or eye, pupil constriction (meiosis) and nasal congestion. The presence of nasal congestion often leads patients to seek ENT opinions resulting in inappropriate ENT procedures.

The rest of this article will focus on updating the reader on cluster headaches as this is the most common form of TACs, the other forms of TACs are covered in previous papers aimed at dentists (2, 20).

Cluster headaches

These are usually unilateral and located to around or above the eye (Figure 1). The pain is severe and has a number of presentations such as burning, tightening or throbbing. The diagnostic criteria can also be seen in Table 2. They may also be further classified into being episodic or chronic in nature. If the patient experiences multiple episodes of cluster headaches with breaks of less than 3 months than they are classified as chronic. Triggering factors include alcohol, nitrate containing food, nitro-glycerine and strong odours such as pain or nail vanish (20).

The pain experienced by patients is often described as the worst pain they have ever experienced, and cluster headaches have been termed ‘suicidal headaches’ as patients have been known to develop suicidal thoughts (2). Cluster headaches more commonly affect men and those than are over the age of 504.

Interestingly, these patients most commonly seek help initially from dentists and there are multiple studies which have found inappropriate treatment on patients in an attempt to relieve the pain of misdiagnosed TACs (1, 20).

Common differential diagnoses:

- Odontogenic pain

- Temporomandibular joint disorder

- Trigeminal neuralgia

Due to the episodic pattern of pain and areas commonly affected by TACs they are often misdiagnosed as toothaches. During the attacks themselves, pain has been known to be experienced in the teeth and jaw (20,21). The jaw pain experienced may be confused with temporomandibular joint disorder.

Treatment

Although the management of cluster headaches is out of the remit of general dental practitioners it is useful that dentists are aware of the management. As with other types of headaches the management of these patients is subdivided into prevention and acute management.

For acute management the evidence supports subcutaneous or intranasal sumatriptan, intranasal zolmitriptan and oxygen (22). For prevention, verapamil is most commonly used. Lithium, melatonin and Topiramate may also be used but the evidence is more limited regarding their use (22,23). Whilst waiting for preventative treatment to work, prednisolone may be prescribed. Due to the side effects of steroids, a unilateral greater occipital nerve block may be performed using either lidocaine or methylprednisolone which has effects lasting up to 4 weeks (2,22).

Sinister headaches

Recent onset of a headache or sudden worsening of headache in a middle-aged patient is rare. If it is associated with sensory or motor neuropathy, nausea, loss of consciousness or other aberrant signs immediate referral to the patients’ general medical practitioner or advice to attend A&E is advised, as exclusion of ischaemic of hameorrhagic stroke and or neoplasia must be undertaken urgently. Exclusion of a recent history of head injury must be excluded and any patient with co morbid poorly controlled or undiagnosed hypertension may indicate a potential stroke risk.

Misdiagnosis:

Common features of neurovascular pain which may mimic odontogenic and complicate diagnosis include (24):

- A deep, throbbing, spontaneous pain which may last up to a few days and be pulsatile in nature may be experienced, similar to how pulpal pain is described.

- The pain is predominantly unilateral.

- Headache is often accompanied by a toothache.

- Periodic and recurrent nature of pain.

- Some autonomic signs may bear a resemblance to a dental abscess such as oedema of the eyelids.

Differentiating between neurovascular and odontogenic pain

There are a number of ways in which the conditions described in this paper can be differentiated from odontogenic pain. (Table 3 at the end of the page) gives an overview of the differentiating features between neurovascular and odontogenic pain to aid dentists in correct diagnosis (25).

A good knowledge base of the signs and symptoms of primary headaches, as well as those related to odontogenic pain will allow an initial diagnosis from the pain history provided from the patient. Specifically, the way the patient describes the type of pain, the location of pain, the triggers of pain, the duration and frequency of the pain will all help form an initial diagnosis just from the patient’s history (Table 3). It is also imperative that the general dental practitioner establishes whether any autonomic features have also been experienced. This will be a key distinguishing factor supporting a neurovascular cause of pain. Secondary to this, a clinical examination supported with radiographs will allow dental pathology to be identified which will help dentists form a definitive diagnosis.

Conclusion

Headaches may present in various ways and it is likely that these patients will present to dentists, especially as the pain may be experienced in their teeth and jaws. Dentists have a responsibility to correctly diagnose pain in the head and neck region. If headaches are suspected an appropriate referral to an OFP service or neurology clinic is favoured as opposed to unnecessary irreversible dental treatment.

Table 1: An overview of the International Classification Disorders, 3rd edition3

|

Primary Headaches

|

1. Migraine 2. Tension-type headache 3. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias 4. Other primary headache disorders

|

| Secondary Headaches |

5. Headache attributed to trauma or injury to head and/ or neck 6. Headache attributed to cranial and/or cervical vascular disorder 7. Headache attributed to non-vascular intracranial disorder 8. Headache attributed to a substance or its withdrawal 9. Headache attributed to infection 10. Headache attributed to disorder of homeostasis 11. Headache or facial pain attributed to disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinus 12. Headache attributed to psychiatric disorder

|

| Painful Cranial Neuropathies, Other Facial Pain and Other Headaches |

13. Painful lesions of the cranial nerves and other facial pain 14. Other headache disorders |

Table 2: Diagnostic criteria as defined by the International Headache Society3

| Migraine without aura |

A. At least five attacks fulfilling criteria B-D B. Headache attacks lasting 4-72 hours C. Headache has at least two of the following four characteristics: 1. Unilateral location 2. Pulsating quality 3. Moderate or severe pain intensity 4. Aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity (eg. walking or climbing stairs) D. During headache at least one of the following: 1. Nausea and/or vomiting 2. Photophobia or phonophobia |

| Migraine with aura |

A. At least two attacks fulfilling criteria B and C B. One or more of the following fully reversible aura symptoms: 1. Visual 2. Sensory 3. Speech and/or language 4. Motor 5. Brainstem 6. Retinal C. At least three of the following characteristics: 1. At least our aura symptom spreads gradually over > 5 minutes 2. Two or more aura symptoms occur in succession 3. Each individual aura symptom lasts 5-60 minutes 4. At least one aura symptom is unilateral 5. At least one aura symptom is positive 6. The aura is accompanied or followed within 60 minutes, by a headache |

| Episodic tension-type headache |

A. At least 10 episodes of headache occurring on <1day/month on average (<12 days/year) and fulfilling the following criteria B. Lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days C. At least two of the following four characteristics: 1. Bilateral location 2. Pressing or tightening (non-pulsating) quality 3. Mild or moderate intensity 4. Not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs D. Both of the following: 1. No nausea or vomiting 2. No more than one of photophobia or phonophobia. |

| Chronic tension-type headache |

A. Headache occurring on >15 days/ month on average for > 3months (>180 days/year, fulfilling criteria B-D. B. Lasting hours to days, or unremitting. C-D. As above |

|

Cluster headaches |

A. At least five attacks fulfilling criteria B-D B. Severe or very severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital and/or temporal pain lasted 15-180 minutes when untreated C. Either or both of the following: 1. At least one of the following symptoms or signs ipsilateral to the headache: a) conjunctival injection and/or lacrimation b) nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhoea c) eyelid oedema d) forehead and facial sweating e) miosis and/ or ptosis 2. A sense of restlessness or agitation D. Occurring with a frequency between one every other day and eight per day |

Table 3: Differentiating between neurovascular and odontogenic pain25

| Migraine | Tension type headaches | Cluster headaches | Acute pulpal pain | Chronic pulpal pain | Periodontal pain | |

| Pain Type | Pulsating |

Pressing, Tightening, Non-pulsating |

Orbital | Throbbing, Aching |

Tender, Aching |

Tender, Aching |

| Pain severity |

Moderate to severe |

Mild to moderate | Severe | Mild to severe | Mild | Mild |

| Location |

Frontotemporal Unilateral |

Frontal Bilateral |

Orbital Unilateral |

Tooth Unilateral |

Tooth Unilateral |

Tooth, Gingivae Unilateral |

| Duration |

4-72 hours

|

30 minutes – 7 days | 15-180 minutes | Seconds to daily | Constant | Varies |

| Frequency | 1/month | 1-30/month | 1-8/day | Variable | Daily | Daily |

|

Autonomic Features |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Triggers | Stress, food, alcohol, hormones, lack of sleep | Stress, Muscle tension | Alcohol, Nitrates |

Electrical or thermal stimulation, percussion of tooth

|

Varies | Lateral pressure, Apical pressure |

Figure 1: Pattern of distribution of pain in primary headaches. Figure adapted from previous paper published in journal by author2.

References

- Renton, T. Tooth-Related Pain or Not? Headache. 2009; 60(1):235-246. Doi: 10.1111/head.13689.

- Chong, M.S, Renton, T. Pain Part 10: Headaches. Dental Update. 2016; 43:448-460.

- The International Headache society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalagia. 2018; 38(1): 1-211.

- Coulthard, P., Horner, K., Sloan, P., Theaker, E. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Radiology, Pathology and Oral Medicine. Third edition. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2013.

- Weatherall, M.W. The diagnosis and treatment of chornic migraine. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015; 6(3): 115-123.

- Nixdord, D.R., Velly, A.M., Alonson, A.A. Neurovascular Pains: Implications of Migraine for the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008; 20(2):221-vii. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2007.12.008.

- Yoon, M.S, Mueller, D., Hansen, N, Poitz, F., Slomke, M., Dommes, P, Diener, H.C., Katsarava, Z., Obermann, M. Prevalence of facial pain in population-based study. Cephalagia. 2009; 30(1): 92-96.

- Smith, J.G., Karamat, A., Melek, L., Jayakumar, S., Renton, T. The differential impact of neuromuscular musculoskeletal and neurovascular orofacial pain on psychosocial function. Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. In press.

- Speciali, J.G, Dach, F. Temporomandibular Dysfunction and Headache Disorder. Headache. 2015; 55(S1): 72-83. doi: 10.1111/head.12515.

- NICE. Migraine. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019. Available online at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/migraine#!references.

- American Headache Society. The American Headache Society Position Statement on Integrating New Migraine Treatments into Clinical Practice. Headache. 2019; 59(1):1-18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456.

- Puledda, F., Messina R., Goadsby, P.J. An update on migraine: current understanding and future directions. J Neurol. 2017; 264(9):2031-2039. doi:10.1007/s00415-017-8434-y.

- Harris, P., Loveman, E., Clegg, A., Easton, S., Berry, N. Systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy for the management of headaches and migraines in adults. Br J Pain. 2015; 9:213-224.

- May, A. Hints on Diagnosing and Treating Headache. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(17):299-308. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0299.

- De Luca Canto, G., Singh, V., Bigal, M.E., Major, P.W., Flores-Mir, C. Association Between Tension-Type Headache and Migraine With Sleep Bruxism: A Systematic Review. Headache, 2014; 54(9): 1460-9. doi: 10.1111/head.12446.

- Glaros, A.G., Urban, D., Locke, J. Headache and temporomandibular disorders: Evidence for diagnostic and behavioural overlap. Cephalalgia. 2007; 27: 542-549.

- Jensen, R.H. Tension-type headache – The Normal and Most Prevalent Headache. Headache. 2018, 58(2):339-345. doi: 10.1111/head.13067.

- Yu, S., Han, X. Update of Chronic Tension-Type Headache. Curr Pain and Headache Reports. 2015; 19(469). doi:10.1007/s11916-014-0469-5.

- List, T., Jensen R. TMD: Old ideas and new concepts. Cephalalgia. 2017; 3331024166866302. doi: 10.1177/0333102416686302.

- Baker, N.A., Matharu, M., Renton, T. Pain Part 9: Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias. Dental Update. 2016; 43(4): 340-352.

- Bahra, A., May, A., Goadsby, P.J. Cluster headache: a prospective clinical study with diagnostic implications. Neurology. 2002; 58(3):354-361.

- Wei, D.Y., Khalil, M., Goadsby, P. Managing cluster headache. Practical Neurology. 2019; 19:521-528.

- Kingston, W.S., Dodlick, D.W. Treatment of Cluster Headache. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2018; 21(Suppl 1): S9-S15. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_17_18.

- Garg, N. Garg, A. Textbook of endodontics. 3rd edition. London: JP Medical Ltd; 2003.

- Balasubramaniam, R., Turner, L.N., Fischer. D., Klasser, G.D., Okeson, J.P. Non-odontogenic toothache revisited. Open Journal of Stomatology. 2011; 1: 92-102.